“I rejoice I am a slave no more, and you are slave no more, Jamaica is slave no more. Amen!” Ex-slave, Thomas Gardner, shouted these words in Jamaica on August 1, 1838, as he celebrated the abolition of the system which had dehumanised his fellow Negroes in the British Caribbean and England for more than 150 years.

With similar jubilation, thousands of ex-slaves, who gathered at town centres and churches in every British Caribbean colony, broke into joyous celebrations after hearing the final words of the Emancipation Declaration, affirming their full freedom from slavery.

The Emancipation Act 1838 was passed by the British Government following a sustained abolition campaign, underscored by bloody slave uprisings in the colonies and widespread public outcry against slavery.

In the midst of the campaign, which lasted from 1780 until 1838, several individuals distinguished themselves as true anti-slavery champions. Among these include:

- Thomas Clarkson

- William Wilberforce

- Joseph Sturge

- William Knibb

- Thomas Burchell, and

- Samuel Sharpe

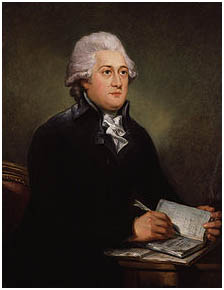

Thomas Clarkson (1760 – 1846)

Thomas Clarkson was a tireless anti-slavery lobbyist whose efforts led to the abolition of the slave trade in Britain in 1807.

Born in Cambridgeshire, England in 1760, Clarkson began lobbying against slavery in his early twenties and in 1787, he became a founding member of the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade.

Clarkson took responsibility for collecting evidence to support the abolition of the slave trade, travelling throughout Britain gathering first hand accounts of slave abuses from sailors and surgeons who travelled on slave ships. These featured prominently in his anti-slavery publications, and included vivid descriptions of the Middle Passage and the techniques used to restrain the slaves. He also obtained some of the devices used to inflict abuse upon slaves, including leg-shackles, branding irons and instruments for forcing open slave’s jaws. Demonstrations of their uses were given during public lectures.

These works provided a firm basis for the first abolitionist speech in the British House of Commons on May 12, 1789, delivered by William Wilberforce. The speech was the beginning of the protracted parliamentary campaign, during which a motion in favour of abolition was moved in the British Parliament almost every year until 1806.

The act abolishing the Slave Trade in British colonies was passed on March 25, 1807 making the trade in slaves illegal in Britain and her colonies.

Clarkson afterwards shifted his focus towards the complete abolition of slavery, becoming a founding member of the Society for the Mitigation and Gradual Abolition of Slavery. Clarkson continued providing evidence against slavery, and spearheaded numerous petitions demanding an end to slavery.

With the passage of the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833, Clarkson cemented his place as a stalwart of the Emancipation movement and earned the gratitude of all individuals freed by his actions.

William Wilberforce (1759 – 1833)

Co-founder and leader of the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, William Wilberforce spent over 20 years lobbying for the abolition of the slave trade in the British Parliament. His keen debating skills helped maintain Parliamentary focus on the subject until the passage of the Slave Trade Abolition Act in 1807.

After being voted into the British House of Commons in 1784, Wilberforce, a devout Christian, resolved within himself to lobbying against the “depraved and unchristian” trade in Parliament. His first speech to Parliament on the subject on May 12, 1789, gave vivid accounts of the atrocities perpetrated against slaves, and won several new supporters for the cause.

Wilberforce went on to move bills for the abolition of the slave trade almost every year between 1790 and 1805, but they were all defeated despite efforts by the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade to win public support.

In 1806, Wilberforce published an influential tract advocating abolition, which resulted in several resolutions supporting abolition being passed by Parliament. On the back of a widespread public campaign, the Abolition Bill was tabled in January 1807, and was subsequently accepted by Parliament with an overwhelming majority.

Following this success Wilberforce turned his attention to lobbying for the abolition of slavery itself.

To this day Wilberforce is regarded as a seminal figure in the anti-slavery cause, whose contributions were truly instrumental in the victories the movement achieved.

Joseph Sturge (1793 – 1859)

Outspoken career activist, Joseph Sturge, dedicated most of his life to the emancipation of slaves in all British territories. Sturge was born in Gloucestershire, England in 1793, and joined the abolition movement in 1823.

When the Anti-Slavery Society, founded in 1827, chose to pursue slavery reforms instead of immediate abolition, Sturge left and formed his own organisation, the Agency Committee, which used among other things, mass leafleting and neighbourhood lectures to agitate for slavery’s immediate end.

After the passage of the Emancipation Act in 1834 freeing all slaves in British colonies, Sturge became an outspoken critic of the six-year apprenticeship period which was to precede full freedom in 1840.

Between 1834 and 1837 he travelled to several British Caribbean colonies gathering information proving that the abuses of slavery were continued during Apprenticeship. He published his findings in two books, which drew widespread criticism of the apprenticeship system, forcing the British Government to implement full emancipation in 1838 – two years earlier than planned.

While in Jamaica, Sturge helped found the Sturge Town free village in St. Ann, providing land and homes for newly freed slaves.

In 1838 Sturge shifted his focus towards ending slavery worldwide, and founded the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, to achieve this end. This Society reaped several successes during Sturge’s lifetime and continued to function even after his death in 1859. The Society is still in operation today under the name Anti-Slavery International, a testament to the tireless effort Sturge displayed during his lifetime towards ending slavery.

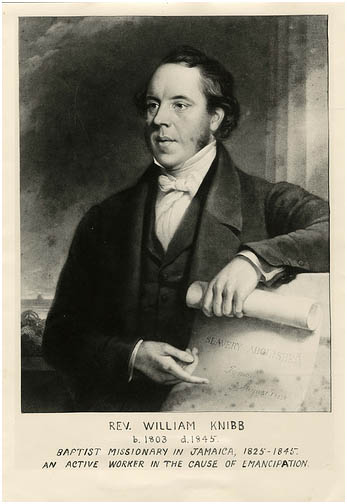

William Knibb (1803 – 1845)

Baptist missionary, William Knibb, emerged as the champion of the Negroes during the early 17th century for his tireless efforts to have slavery abolished.

Knibb arrived in the island in 1824, and like his counterpart, Thomas Burchell, he quickly became an outspoken critic of slavery, deeming it “glutted with crimes against God and man”. Knibb gained the respect of the slaves after publicising the unfair arrest of a slave Sam Swiney.

Swiney was convicted and flogged for preaching without a licence, when in fact he was only praying. Knibb published full details of the case in an island newspaper, which led to the dismissal of the magistrates involved.

After the Great Jamaican Slave Rebellion of 1832 Knibb was arrested on suspicion that he helped instigate the rebellion. After his eventual release, Knibb continued his outspoken criticism of slavery, even in the face of death threats and the destruction of his church at Falmouth, Trelawny.

In 1832 Knibb travelled to England where he appeared before committees of both Houses of Parliament, outlining the atrocities of slavery and the difficulties facing missionary groups. He also toured England and Scotland, preaching about the oppression of the slaves.

Knibb spoke with such fervency that he won numerous supporters for the anti-slavery cause, leading to the passage of the Emancipation Act of 1832, which granted freedom to all slaves in British colonies.

After returning to Jamaica, Knibb continued working to improve the social conditions facing Negroes. He founded the free villages, Wilberforce (now Refuge), Kettering and Granville, all in Trelawny, and also established several chapels and schools all over the island.

After his death in 1845, Knibb remained the unmatched champion of the slaves. For his efforts he was awarded one of Jamaica’s highest civil honours, the Order of Merit, at the 150th anniversary of slavery in the British colonies.

Thomas Burchell (1799 – 1846)

Baptist Missionary Thomas Burchell was instrumental in convincing the Baptist Missionary Society (BMS) and other social organisations to lobby the British Parliament to end slavery in its Caribbean colonies.

Burchell arrived in Jamaica from England in 1822, and quickly developed a deep hatred for slavery because of the abuses slaves endured. He wrote several letters to the BMS criticising slavery, helping to spur the organisation to join with the Society for the Abolition of Slavery in lobbying the British Government to end slavery.

In 1827 one of Burchell’s letters was published in a popular British magazine and when news of the letter reached Jamaica, the local planters had Burchell arrested for sedition. The planters offered to drop the charge if Burchell would make a public apology for his statements, but Burchell refused. The case was eventually discontinued, but Burchell earned folk hero status among the slaves for his firm anti-slavery stance.

Burchell’s reputation caused him to be arrested as an instigator after the Great Slave Rebellion of 1832. He was released later that year, and afterwards travelled to Britain where he began working with the Anti-Slavery movement, providing firsthand details of the atrocities of slavery. This information was heavily relied upon by members of the Anti-Slavery movement to gain the passage of the Emancipation Act of 1832.

Returning to Jamaica in 1833, Burchell, like other Baptist missionaries, purchased large tracts of land and divided them into smaller lots, which he sold to the ex-slaves, allowing them to form free villages. Burchell himself was the founder of the Bethel Town and Mount Carey free villages in Montego Bay, St. James. Before his death he founded several churches, schools, and health centers all over the island catering to the ex-slaves.

Edward Jordon (1800 – 1869)

Newspaper editor, statesman, and political activist, Edward Jordon helped galvanize public opinion against slavery in Jamaica among the free mulatto class using his newspaper,The Watchman.

Jordon, a Jamaican mulatto, enjoyed more privileges and a higher social status than the slaves, but was barred from enjoying basic civil rights, such as voting or giving evidence in court, because of his non-white status. Jordon emerged as an outspoken member of the mulatto group, actively using his newspaper to lobby for their interests. He surprised many, however, by also being very sympathetic to the slaves, regularly publishing articles criticizing the harsh treatment they experienced.

In 1832 he printed an editorial calling for the planters to “knock off the fetters, and let the oppressed go free”. In response the Jamaican planters had Jordon tried for sedition, which carried the death penalty. Though the charge was eventually dropped, Jordon spent six months in prison before his release.

Jordon continued campaigning against slavery even after his release, and after winning the Kingston seat in the House of Assembly in 1835 he helped implement the articles of the Emancipation Act of 1834.

Jordon went on to have a prolific career in public and private service. He founded another newspaper, The Morning Journal, and became manager of the Kingston Savings Bank, and director of the Planters’ Bank. At various times he held the offices of Mayor and Custos of Kingston; Speaker of the House of Assembly and Colonial Secretary. A memorial statue of him was unveiled in Kingston in 1875, and can be seen today in the St. William Grant Park in downtown Kingston.

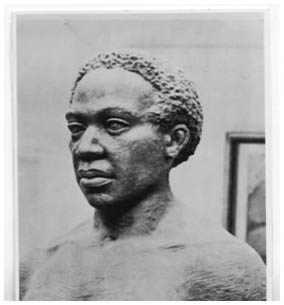

Sam Sharpe (circa 1801 – 1832)

National hero, Samuel Sharpe, was an outstanding leader whose drive to dismantle the system of slavery helped strengthen the movement towards the abolition of slavery in all British colonies.

Sharpe was born in the early 1800s, at the height of Jamaica’s sugar and slave economy, in which Negroes were regularly brought into the island and sold as slave labourers, mostly to sugar plantations.

Some owners, including Sharpe’s, were sympathetic to the slaves, treating them humanely and allowing them to be educated. As Sharpe grew to adulthood he became a popular Baptist preacher and an outspoken anti-slavery critic.

In 1831 Sharpe conceived a radical plan to end slavery in Jamaica by having the slaves strike on December 28 and refusing to work until wages were negotiated. Sharpe maintained however, that the slaves should avoid violence at all costs. The plan was readily accepted and gained supporters in most of the western parishes.

However, on December 27 some slaves set fire to buildings on the Kensington Estate, sparking outbreaks of violence on other plantations, and foiling Sharpe’s plan for passive resistance. In retaliation the government called out the armed forces, who brutally put down the insurrections on all estates, killing over 500 slaves. Sharpe was later tried and hanged for his role in instigating the revolt.

Despite the number of lives lost, the size of the rebellion forced the British Government to address the widespread anti-slavery sentiment in the island.

In 1833 the British House of Commons formed a committee to pursue the abolition of slavery in all British colonies, and the following year the Emancipation Act was passed, stipulating that slavery would end on August 1, 1834.

For his contribution to the anti-slavery movement, Sharpe was posthumously conferred with the nation’s highest honour, the Order of National Hero, in 1975.

His face today appears on the Jamaican fifty-dollar bill and a statue of him was constructed at Sam Sharpe Square in St. James.